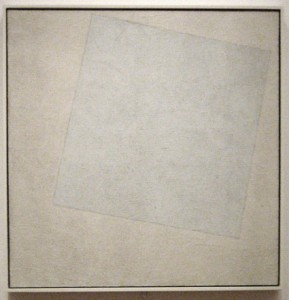

Kazimir Malevich – ‘Suprematist_Composition – White on White’, oil on canvas, 1918, Museum of Modern Art

One reason why there are so few decent books on modernism — pace the often excellent books and studies of individual modernist writers, painters and thinkers — is that modernism is not a term that can be clearly defined or dated. Every attempt brings risk: why this historical period as opposed to another, why this trend and not one that paralleled or preceded it? Can modernism have a specific date and place? Is there one modernism or many?

What is excluded is just as important as what is included. Should Dada and Futurism be included or should they be seen as unique challenges within the modernist movements happening across Europe. Should Vorticism and Russian Futurism be included; how should one place the short-lived collective OBERIU along with Suprematism and the artistic and other literary experiments happening across Eastern Europe and Russia, and in the early years of the Soviet Union? How to they fit into the idea of modernism? And why has modernism today retreated from the scene? Why have we returned to tired forms and nostalgia?

To understand what modernism is, it may be best not to seek a positivist account. It cannot be reduced to a defined historical period, as a part of the natural progression of art and history; or amongst its most implacable foes, as a conspiracy by academics and dealers looking to secure tenure and make money by telling people that plotless novels and blank canvases were superior to good-old-fashioned plot-driven works and recognizable landscape paintings.

Instead, I would like to propose that modernism can only be understood as a result of the tensions that emerged within the Renaissance the later Enlightenment, in what T.S. Eliot called the ‘dissociation of sensibility,’ where the individual was now in a world were the old verities were gone, or if not completely disappeared were nevertheless under increasing scrutiny. But what was to replace the old certainties was uncertain. At the same time this was happening, there was a growing shift to living in what we would call urban environments, where life was tuned to new kinds of economic, social and political realities.

Hegel in his Phenomenology of Mind outlined the psychic cost of this dissociation. Where Man could once ground the self on what were once universally accepted certainties, that was not the case anymore. In the section ‘Freedom of Self-consciousness: Stoicism, Scepticism and the Unhappy Consciousness,’ Hegel outlines how the self is now not a secure, unchanging thing that can be objectively observed, but is one in dialectical flux:

Sceptical self-consciousness thus discovers, in the flux and alternation of all that would stand secure in its presence, its own freedom, as given by and received from its own self. It is aware of being this of self-thinking thought, the unalterable and genuine certainty of its self. This certainty does not arise as a result out of something extraneous and foreign which stowed away inside itself its whole complex development; a result which would thus leave behind the process by which it came to be. Rather consciousness itself is thoroughgoing dialectical restlessness, this mêlée of presentations derived from sense and thought, whose differences collapse into oneness, and whose identity is similarly again resolved and dissolved — for this identity is itself determinateness as contrasted with non-identity. This consciousness, however, as a matter of fact, instead of being a self-same consciousness, is here neither more nor less than an absolutely fortuitous embroglio, the giddy whirl of a perpetually self-creating disorder. This is what it takes itself to be; for itself maintains and produces this self-impelling confusion. Hence it even confesses the fact; it owns to being, an entirely fortuitous individual consciousness — a consciousness which is empirical, which is directed upon what admittedly has no reality for it, which obeys what, in its regard, has no essential being, which realizes and does what it knows to have no truth. But while it passes in this manner for an individual, isolated. contingent, in fact animal life, and a lost self-consciousness, it also, on the contrary, again turns itself into universal self-sameness; for it is the negativity of all singleness and all difference. From this self-identity, or rather within its very self, it falls back once more into that contingency and confusion, for this very self-directed process of negation has to do solely with what is single and individual, and is occupied with what is fortuitous. This form of consciousness is, therefore, the aimless fickleness and instability of going to and fro, hither and thither, from one extreme of self-same self-consciousness, to the other contingent, confused and confusing consciousness. It does not itself bring these two thoughts of itself together. It finds its freedom, at one time, in the form of elevation above all the whirling complexity and all the contingency of mere existence, and again, at another time, likewise confesses to falling back upon what is unessential, and to being taken up with that. It lets the unessential content in its thought vanish; but in that very act it is the consciousness of something unessential. It announces absolute disappearance but the announcement is, and this consciousness is the evanescence expressly announced. It announces the nullity of seeing, hearing, and so on, yet itself sees and hears. It proclaims the nothingness of essential ethical principles, and makes those very truths the sinews of its own conduct. Its deeds and its words belie each other continually; and itself, too, has the doubled contradictory consciousness of immutability and sameness, and of utter contingency and non-identity with itself. But it keeps asunder the poles of this contradiction within itself; and bears itself towards the contradiction as it does in its purely negative process in general. If sameness is shown to it, it points out unlikeness, non-identity; and when the latter, which it has expressly mentioned the moment before, is held up to it, it passes on to indicate sameness and identity. Its talk, in fact, is like a squabble among self-willed children, one of whom says A when the other says B, and again B, when the other says A, and who, through being in contradiction with themselves, procure the joy of remaining in contradiction with one another.

Later he will add:

Hence the Unhappy Consciousness the Alienated Soul which is the consciousness of self as a divided nature, a doubled and merely contradictory being.

This unhappy consciousness, divided and at variance within itself, must, because this contradiction of its essential nature is felt to be a single consciousness, always have in the one consciousness the other also; and thus must be straightway driven out of each in turn, when it thinks it has therein attained to the victory and rest of unity. Its true return into itself, or reconciliation with itself, will, however, display the notion of mind endowed with a life and existence of its own, because it implicitly involves the fact that, while being an undivided consciousness, it is a double-consciousness. It is itself the gazing of one self-consciousness into another, and itself is both, and the unity of both is also its own essence; but objectively and consciously it is not yet this essence itself — is not yet the unity of both.

An important part of modernism is recognizing this new sense of the self that emerged. While many books about the Renaissance and the Enlightenment tend to place positive weight on the emergence of what we would call modern individualism that arose out of the collapse of the old ways of thinking about persons and their relationship to society and religion, these thinkers and writers have often downplayed or ignored the tensions and contradictions that arose. In the effort to undermine old certainties, Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers often could not ground the new certainties any better. If old certainties were argued to be set on unexamined or arbitrary foundations, the new ones were many times set upon ones that were as unstable and prone to collapse when subjected to the same scrutiny given to the ones now removed. The self and its place in this new world was as uncertain as the foundations on which the new order was trying to set itself upon, hence Hegel’s sense that self-consciousness was unhappy when it became aware of its divided and contradictory being.

Kierkegaard recognized one consequence of this dissociation of sensibility and that is the tendency of persons to seek some basis on which to ground themselves. One way of doing so is by absorption into the anonymous urban mass. Kierkegaard recognized the consequence of this absorption, which in his A Literary Review, he called ‘levelling.’ The danger in this levelling is that it removes the will of persons to examine themselves and gives rise to inauthentic selves based on what is external. As he was to put it in The Sickness unto Death:

A human being is spirit. But what is spirit? Spirit is the self. But what is the self? The self is a relation that relates itself to itself or is the relation’s relating itself to itself in the relation; the self is not the relation but is the relation’s relating itself to itself. A human being is a synthesis of the infinite and the finite, of the temporal and the eternal, of freedom and necessity, in short, a synthesis. A synthesis is a relation between two. Considered in this way a human being is still not a self…. In the relation between two, the relation is the third as a negative unity, and the two relate to the relation and in the relation to the relation; thus under the qualification of the psychical the relation between the psychical and the physical is a relation. If, however, the relation relates itself to itself, this relation is the positive third, and this is the self.

By the late-19th Century, this feeling of the self under threat, of the ennui produced by the self’s perilous relationship to mass society, of at any moment it being swallowed up, was memorably described by Coleridge in his Biographia Literaria as the feeling one gets when missing a step on a darkened staircase.

Heidegger in Being and Time will take this idea of levelling to describe the anonymous ‘they’ of das Man, that of modern urban mass culture that directs persons to superficial externalities:

In this averageness with which it prescribes what can and may be ventured, it keeps watch over everything exceptional that thrusts itself to the fore. Overnight, everything that is primordial gets glossed over as something that has long been well known. Everything gained by struggle becomes something to be manipulated. Every secret loses its force. This care of averageness reveals in turn an essential tendency of Dasein which we call “levelling down” of all possibilities of Being.

We might call this public opinion or received wisdom, an all-to-easy set of prescriptions for our selves and our agency, that are external to us and un-reflected upon. This is why today, in my opinion, there is a nostalgia for the old forms, for novels written in the modes from the 19th century with its comfortable psychology; for serious music that tonally mimics earlier styles.

Modernism brings this tension to the fore, of Hegel’s dialectical self and its relation to the world with the pressures of sinking the self into modern society’s anonymous levelling of spirit. Kierkegaard waned of the dangers of the levelling affect of the public, of which nostalgia is one such consequence :

The public, however, is an abstraction. To adopt the same opinion as these or those particular persons is to know that they would be subject to the same danger as oneself, that they would err with one if the opinion were wrong, etc. But to adopt the same opinion as the public is treacherous consolation, for the public exists only in abstracto.

Modernism resists this levelling of the public, of the treacherous consolation of the old forms.