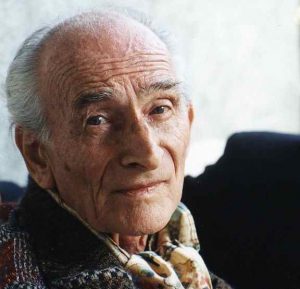

Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, known to most as Balthus, remains the most enigmatic of painters. His work seems outside the major visual movements of the past century. His is a modernism of a revival of old masters techniques with the psychological acumen of Freud. His paintings work like a foreign language, the meanings hidden until we learn to read them properly. Yet, nothing is truly hidden in Bathus’s paintings, except the viewer’s own prejudices which causes many to be drawn up short when coming across his work.

Balthus is too often regarded as a painter of prurient eroticism, of young girls in provocative poses. This is mistaking the surface for what the paintings are about. Are Thérèse on a Bench Seat or Thérèse Dreaming really nothing more than paintings of eroticised adolescence? Or is there something more going on? It would be best to contrast these works with Surrealism. Breton in his manifesto described Surrealism as, “Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express — verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner — the actual functioning of thought.” Balthus is very much interested in the psychological. Unlike Dali, Andre Masson or Rene Magritte, however, Balthus is not interested in depicting the mechanisms of the psychic automatism of thought. Balthus is instead a contemporary of the novelist André Gide and Charles Fourier’s 19th century utopianism.

For Balthus, adolescence is a time where children come into their own. It has its own dynamism, that frisson of energy when a new self emerges and possesses the world around it. Wuthering Heights is a keystone for Balthus. Emily Brontë’s novel is a depiction, if in hysterical fashion, of how adolescence creates its own customs and sense of time. Thérèse in the paintings is a depiction of that adolescent vitality and psychic emergence, where erotic energy is channeled into what Guy Davenport, in his provocative A Balthus Notebook, describes as an “an endless afternoon of reading, playing cards, and daydreaming.” For Balthus — as for writers Alain-Fournier and Cocteau, as well — children live in their minds and contour the world and themselves around those games, afternoons and daydreams. There is an eerie stillness in emerging adolescence that Balthus captures. We are glimpsing, just for a moment, that interior self-sufficiency of the adolescent, where body, mind and world are united and creating a unique space of possibilities.

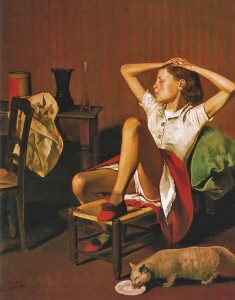

Pause for a moment over Thérèse. Balthus paints her leaning back in an armchair. Her face is apparently turned toward the viewer, but not (if one looks closely) focused directly either on the painter, whom she is supposedly gazing towards, or us. Her pose is relaxed and understated. Raised and crossed on top her right leg, her left is relaxed with her left hand placed on the knee. Balthus’s capturing of light on her legs and face, the careful working out of such details as her hands, clothing and Thérèse’s gaze all suggest a girl within her own world. The armchair, the table and its wrinkled covering, the wall behind her are now part of the interior world of Thérèse. Thérèse is wholly within herself, looking at herself. She is far removed from Watteau’s Diana Bathing. Diana, while alone like Thérèse, is never unaware of the gaze of another. Thérèse cares not a wit for another’s gaze. Balthus’s adolescents with their provocative poses are not seeking to be gazed at, but instead gaze into their own world. The world around them is then remade in that interior view. One is reminded of Courbet’s portrait of his sister, Juliette, who possesses the same self-satisfied gaze and glance one finds in Balthus. Balthus obviously was influenced by that work.

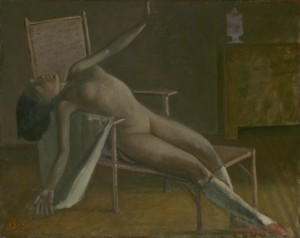

Nude on a Chaise Longue is another painting that captures this moment, a variation, I believe, on the earlier Thérèse paintings. Here a female figure wearing only white knee socks and red slippers is on a chaise longue. She is stretched across the longue with her head back, eyes closed and one arm raised above her and another down towards the floor. Her hair is loose. The colours are muted. The female figure’s age is indeterminate. Like Thérèse, the female figure is within her own world. Body, mind and place are one within the painting. Possibilities of an emerging physical, psychological and sexual realm abound, but never is one realm privileged over another. Balthus’s old master techniques, his chiaroscuro lighting effects, his colour palate and his near architectural placement the objects in the room and the placement of the female figure bring all three realms together.

It is a mistake to see Balthus as focusing only on the sexual. Balthus often said that his paintings had no overt sexuality. I think he was not so much denying such sexuality existed, but that is was not the only thing his paintings were about, or even what they were about at all. The sexuality in Balthus is never vulgar or cheap. It is strangely protective as the gaze of all the girls is private and inward, never outward or beckoning. It is only the person who fails to understand or to truly experience what Balthus is doing and instead forces Balthus into a single meaning — in most cases today one of prurience and admonition against adolescence having any kind of healthy and meaningful interior life that is not circumscribed by adult expectations or worries over innocence and experience — that will miss what makes Balthus important.