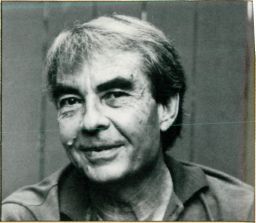

This being the centenary of the birth of Milton Babbitt, one expects that celebrations of his work and legacy would be in order. So why the silence?

Milton Babbitt is one of America’s greatest composers; and one of the most neglected in performance halls. While the Julliard School’s Focus! Festival recently celebrated the centenary of Babbitt’s birth (Babbitt taught there for 37 years) and pianist Augustus Arnone performed Babbitt’s complete solo piano works, there are few other celebrations of his works planned.

One reason is the fearsome reputation of Babbitt and his music. Babbitt is said to be a composer of ‘difficult’ music. That alone gives some pause. Many have strong, negative opinions of his work without ever having heard a single note. Then there are the essays, ‘Who Cares if you Listen?’ published in High Fidelity (1958) and ‘Some Aspects of Twelve-Tone Composition’ (1955) where he famously argued that, ‘twelve-tone music suffers only slightly more than other ‘difficult,’ ‘advanced’ music — to the extent that the label itself supplies a basis for automatic rejection.’ One only has to replace ‘twelve-tone music’ with ‘serial music’ and one captures the feeling of most music listeners today toward Babbitt and his works.

That is unfortunate because Babbitt’s music is hardly difficult and its rejection says much about the state of contemporary musical performance.

Let’s take a look for a moment at Babbitt’s High Fidelity piece, one which is often pointed to as an example of everything that is wrong with Babbitt and with contemporary serious music. First off, the title was not Babbitt’s. It is, in fact, ‘The Composer as Specialist.’ The editors at High Fidelity wanted something more provocative. Without telling Babbitt, the editors changed the title. To this day, that title gives many the wrong impression of what Babbitt was arguing. Here is an excerpt:

The unprecedented divergence between contemporary serious music and its listeners, on the one hand, and traditional music and its following, on the other, is not accidental and- most probably- not transitory. Rather, it is a result of a half-century of revolution in musical thought, a revolution whose nature and consequences can be compared only with, and in many respects are closely analogous to, those of the mid-nineteenth-century evolution in theoretical physics The immediate and profound effect has been the necessity of the informed musician to reexamine and probe the very foundations of his art. He has been obliged to recognize the possibility, and actuality, of alternatives to what were once regarded as musical absolutes. He lives no longer in a unitary musical universe of “common practice,” but in a variety of universes of diverse practice.

This fall from musical innocence is, understandably, as disquieting to some as it is challenging to others, but in any event the process is irreversible; and the music that reflects the full impact of this revolution is, in many significant respects, a truly “new” music, apart from the often highly sophisticated and complex constructive methods of any one composition or group of compositions, the very minimal properties characterizing this body of music are the sources of its “difficulty,” “unintelligibility,” and isolation. In indicating the most general of these properties, I shall make reference to no specific works, since I wish to avoid the independent issue of evaluation. The reader is at liberty to supply his own instances; if he cannot (and, granted the condition under discussion, this is a very real possibility) let him be assured that such music does exist.

If one takes a moment to read these words carefully, one discovers that there is not much to disagree with. I am most in agreement with his argument that today’s composer is ‘obliged to recognize the possibility, and actuality, of alternatives to what were once regarded as musical absolutes. That there exists not a single set of agreed upon practices, but a variety of ‘universes of diverse practice.’

One of the challenges of modern serious music, especially at music that is labeled ‘difficult’, is that it requires listeners to abandon searching for recognizable tonal reference points. These points are ones that have been drilled into people’s ears and reinforced by repeated performances of agreed-upon important classical works. If one comes to a piece by Babbitt expecting to hear a composition in the style of Beethoven or to hear melodic motifs similar to what one finds in Schumann or Debussy, then one will be lost. That is not to say all that came before is abandoned, only that there are now other ways to compose works, new vocabularies open to the composer to use.

Babbitt’s music, as with much other serious music of the 20th century (atonal, twelve-tone, microtonal, electro-acoustic, etc.), puts these new musical vocabularies or ‘universes of diverse practice’ at the centre of the work; and places unique demands upon listeners:

This is not necessarily a virtue in itself, but it does make possible a greatly increased number or pitch simultaneities, successions, and relationships. his increase in efficiency necessarily reduces the “redundancy” of the language, and as a result the intelligible communication of the work demands increased accuracy from the transmitter (the performer) and activity from the receiver (the listener). Incidentally, it is this circumstance, among many others, that has created the need for purely electronic media of “performance.” More importantly for us, it makes ever heavier demands upon the training of the listener’s perceptual capacities.

I liken the demands made by contemporary serious music on the listener to that made by modernist literature on readers. If one comes to the works of Joyce and Beckett, or Gaddis and Gass, for example, or to the poetry of Paul Celan or H.D., expecting to read them in the same way, or to operate in a similar fashion, as 19th century novels and poetry, then one will be thrown for a loop. It is still common for people today to react negatively to modernist literature; just as it is common for people to have a similar reaction to ‘difficult’ music. How many times have such works been dismissed – with a great deal of anger in some cases – as elitist, the artist producing works cut off from the greater world and arrogantly asserting themselves above the common man.

Take a moment to listen to these two early pieces by Babbitt:

These works showcase Babbitt’s extension of the twelve-tone idiom. What about them is exactly ‘difficult’ or elitist? Where are they ugly, as I’ve heard other claim?

When one listens to other Babbitt compositions, such as All Set, one hears not difficulty, but joy and sly humour. And the music swings!

Even knottier works such as Tableaux for piano from 1973 with its rapidly unfolding contrapuntal lines never feels forced or academic. It is engaging in the deepest sense of the word:

So why is Babbitt’s music not played more often in the concert repertoire?

The late Charles Rosen in Freedom and the Arts: Essays on Music and Literature, makes a point that new music requires champions and repeated performance to become understandable to an audience.

Too often, today’s orchestra’s and chamber groups shy away from doing this. One is a fear of offending the audience. With many orchestras and chamber groups in the United States and Canada financially struggling, symphony and chamber music board members will insist on sticking to what is familiar. That is why every year one hears the same pieces and composers, the same operas performed. I had one board member tell me that if they were to program new works they were guaranteed to see about a quarter of their long-time subscribers cancel their support. Why risk such a financial loss?

And in those rare times when a new piece is performed, it is often done badly. New works need extensive rehearsals for the performers to understand what the composer wants to achieve, to familiarize the players with the new tonal language before them. And once mastered, those works need to be played often so that audiences can orient themselves and navigate these works.

Rosen remarks how he conveyed his excitement and wonder to Boulez at a performance of a chamber work by Harrison Birtwhistle that Boulez conducted. “Boulez explained: ‘We had thirty-five rehearsals.’” Later, when Rosen saw a performance of Alban Berg’s Lulu conducted by Boulez, and was fascinated by how the orchestra seemed to know the opera by heart and executed it with amazing confidence, again Boulez remarked that he was able to secure forty-five recording sessions. It was only by repeated rehearsals, by the orchestras and chamber groups working their way through the difficult piece before them, did the musicians achieve the mastery and understanding needed to make the works understandable to both themselves and the audience.

“Is it any wonder that the public finds difficult contemporary music so irritating. However, since Beethoven, it is the difficult music that has eventually survived most easily; originally unintelligible Wagner, Strauss, Debussy, Stravinsky, and all the others that were so shocking are now an essential part of the concert scene. Some of this music is accepted because of its prestige; an average audience would find Beethoven’s Grosse Fugue for string quartet as annoying as Schoenberg or Stockhausen if they were not told the name of the composer.” (184)

Rosen adds that even up to the 1950s, there were towns in the United States that would cancel performances by the famed Budapest Quartet if they got a hint that the musicians might play a late Beethoven quartet.

Not much has changed. Few concert halls or chamber groups will invest the time needed to learn a new piece of ‘difficult’ contemporary music and risk the audience’s puzzlement or resentment; or to make such works a standard part of the repertoire and thereby help audiences become accustomed to such works.

But without the commitment in bringing new works to musicians and audiences, works by such composers a Babbitt – and many others, sadly – will remain rarely heard or given a chance to find an audience.