I remember the Guy Davenport story, actually a novella and the first of his three great novellas, which made me a lifelong admirer of his fictions. It was the opening of ‘The Dawn in Erewhon’ from his first collection, Tatlin!

The Dutch philosopher Adriaan Floris van Hovendaal was arranging the objects on his table, a pinecone to remind him of Fibonacci, a snail’s shell to remind him of Ruskin, a drachma to remind him of Crete. He had been thinking all morning of time, which was nothing, or was the direction of being, or was a dimension of the world and therefore spatial, or was the deference whereby an effect followed rather than preceded or was simultaneous with its cause, or was but sequence and nothing more.

This opening stopped me, not because I was flummoxed by the references and learning packed into that single paragraph. My reading in university at the time I discovered Davenport’s fictions was delightfully eclectic and catholic, with the chaotic reverie that comes from youth and wanting to devour all. Along with my assigned readings from professors, I devoured the densest of philosophical works, Schopenhauer to Heidegger, the ancient Greeks to Wittgenstein; high modernists as Wyndham Lewis, Virginia Woolf, Joyce and Beckett, to name a few, and works science fiction and detective stories.

Davenport’s opening captured the world I was living in at the time and its excitement. As I read on, going to the university library to check upon some person or idea Davenport referenced, I grew enchanted with how Davenport told the story of van Hovendaal, whom I learned Davenport modeled after Ludwig Wittgenstein and the retelling Samuel Butler’s Erewhon. This was not writing, I thought, but writing as a work of art. The novella’s disjunctive style was as important as the story; the juxtapositions of different ideas and thinkers were meant to startle one into new ways of seeing and thinking about things.

Once, reading by a campfire, he had an intuition of the bog men inspecting their bone hooks and written blades by the glow of peat. He had thought of Rembrandt, of the preciousness of glass, the interior smugness of the Dutch. Rembrandt was candlelight, stovelight.

Vermeer was windowlight reflected from canals. Hobbema, the light before rain. The north had all its light sifted through forest leaves, and has never forgotten it. Only Dūrer dreamed of real light.

I cannot look at those painters to this day without Davenport’s illumination of the different kinds of light each painted. No one wrote like this; no one today writes like Davenport.

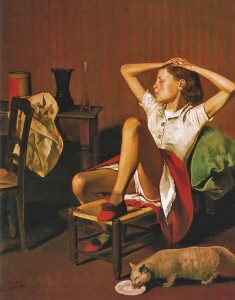

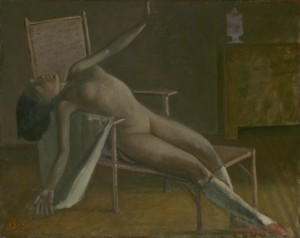

Each time I read his fictions and novellas, I’m amazed not just at the erudition behind them, but how I’m startled anew by some piece of information Davenport places in this story, linking together thinkers and ideas that brings about some new insight. Davenport often notices something mundane, something that has always been there, but that throws into a new light an artist’s whole work. Take for instance Balthus, whom Davenport has probably written the only good studies of this painter, both in his Balthus Notebook and the short essay ‘Balthus’ in his collection Every Force Evolves a Form and from which the passages below are taken:

The only clock I can find in Balthus is on the mantel of The Golden Days of the Hirschhorn, and its dial is out of the picture. Balthus’ children have no past (childhood resorbs a memory that cannot yet be consulted) and no future (as a concern). They are outside time.

Charles Fourier concocted an elaborate philosophy to discover human nature and invented a utopian society to accommodate it, a society of children organized into hives and roving bands. Adults were, so to speak, to be recruited from the ranks of this aristocracy.

The linking of Charles Fourier with Balthus is marvelous and revelatory. Balthus and Fourier are utopians. Both celebrate and revivify the imagination and physical and sensuous life. As if often the case with Davenport, as it is with Balthus, it is those moments of adolescent reverie and imagination, combining Eros and sensuous energies, which remake the world. There is a passage in Davenport’s stunning Apples and Pears that captures this moment and serves as a touchstone for what Davenport hoped to achieve in his fictions and essays:

Rilkean angels, complex essences in a wind of light, fibrous with articulate memories, accidental events enriched into significance, a cherished smile, a long afternoon, a concupiscent dream, disappointments salvaged by courage, are the quiring that Fourier saw as a destiny of attraction. They are harmonies of essences. They are kin to us.

Davenport is not much read now. Many of his books have gone out of print and none of his stories, to my knowledge, appear in collections of American short fiction. He has his admires, students who attended his lectures and classes at the University of Kentucky, and other writers. Samuel R. Delany has written that Davenport is one of a select group of writers who “each reaching in an entirely different direction, achieve a sentence perfection that dazzles, chills and – sometimes – frightens: William Gass, Joanna Russ, Guy Davenport and Ethan Canin.”

What explains Davenport’s near vanishing from the literary scene? Davenport’s fictions feature many instances, sometimes alluded to and sometimes explicit, of boys and young men in homoerotic relationships. This part of Davenport’s works throws up barriers to some readers, although I have found many, who while turning away from Davenport’s work, have no problem with Nabokov’s more morally disturbing Lolita.

What may be going on is that many mistake Davenport’s boys and men as pornographic images, much as Balthus’ paintings are reduced to being nothing more than the work of a dirty old man who liked “young girls showing their knickers,” as one person told me when Balthus’ name was mentioned. As a scholar and translator of ancient Greek, Davenport knew how Eros and philosophy were closely tied. Eros, agapē and love fill Platonic dialogues. The handsome Alcbiades desires to sleep with Socrates only to have Socrates artfully put him off. Still, it is this erotic element in Plato that is turned to the highest of philosophical arguments and speculation.

Dialogue between the master and the student, between the older Socrates and the younger men and boys whom he speaks and debates with, is electrically charged with erotic energies. There is no getting away from that. George Steiner in his Lessons of the Masters puts it memorably: “A ‘master class,’ a tutorial, a seminar, but even a lecture can generate an atmosphere saturated with tensions of the heart. The intimacies, the jealousies, the disenchantment will shade into motions of love or of hatred or into complicated mixtures of both . . . Over the millennia, in countless societies, the teaching situation, the transmission of knowledge, of techniques and of values (paideia) have knit in intimacy mature men and women on the one hand, adolescents and younger adults on the other.” From the Platonic academy to British public schools, from the Athenian gymnasium to seminaries, homoeroticism and education are intimately linked.

Such relationship are fraught with risk. Rousseau knew the dangers of amour proper, that it can become toxic and self-defeating. But if moved in healthier directions, amour proper would help develop rational capacities and more healthy relationships amongst persons. Davenport’s fictions with their Fourierist utopianism are a plea for a healthier relation between both imagination and Eros. Davenport knew that his fictions were likely to be controversial. In his anthology collection Twelve Stories, he wrote that he excluded his longer novella and novel-length works (The Dawn in Erewhon, Apples and Pears and “Wo es war, soll ich werden”) as they were often misunderstood. Too many fixed on elements that are trivial. While never stated outright by Davenport, he could only mean the homoerotic elements of the works. Still, he held onto the hope that there might someday be a readership for these complex fictions: “Another age, beyond our end-of-century comstockery and Liberal puritanism, may find these works interesting, aber freilich nicht wahrscheinlich.”