Museums are contested spaces. Never stable either in the physical space a museum occupies or its purpose. Foucault described the museum as a heterotopia, a space of difference in which the elements of culture are suspended or reversed. At any moment the objects displayed can take on radically different meanings, where what is thought eternal can be upended and questioned. The same goes for the building. Any new addition or change, especially a radically architectural one, can bring about a new debate about the role of the museum. A break with ‘tradition’ can call even the museum’s ultimate function in question, especially its role as a space of preservation.

Hegel in his lectures on aesthetics make the point that when the life of art has been diminished in secular society, where art cedes its place to philosopher for contemplating the Absolute, the museum becomes a place not for art’s revitalization but for its mere preservation; where preservation here means that art is largely separate from living culture. It become dead, depoliticized. Taking his lead from Hegel, Adorno would later describe the museum as the “family sepulchers of works of art.” It is only when art can break out into real life once more can art become relevant again, both politically and socially.

The strong reactions that often accompany discussion about museums is around this very question. What is its role: one of dead preservation, in the sense of Hegel and Adorno, or where Foucault envisions the museum as place of permanent critique with the past as the museum embodies the critical apparatus of the Enlightenment in order to look back upon itself. (The paradox is that it can only be done within the very Enlightenment values and critical apparatuses it homes to subject to critical examination. Foucault is sensitive to this . . . but that tension to be commented upon at another time)

It will be interesting to see what the reaction will be to the Royal Ontario Museum’s move to not only change its logo, but its mission as a museum. This is how Janet Carding, ROM director and CEO described what was happening: “We’re changing our visual identity now to focus on the Museum as an indispensable resource. We’re placing the ROM’s encyclopedic collections, research and curatorial expertise at the heart of the new brand, and showing how, through the ROM, people can connect to their world.”

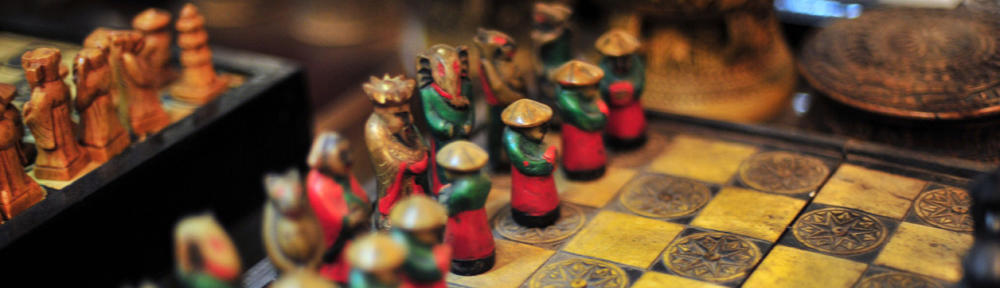

The logo makes not reference to the structure of the building or its recent Daniel Libeskind addition which provoked many negative reaction is the local press and public. Instead, it is to symbolize “access and dynamism” to the museum’s collections. If the ROM’s history is any guide, there is nothing to suggest the ROM will not continue to display artifacts in glass cases with many exhibits wrenching the objects out of context and history. As a museum, the ROM feels more like Lefebvre’s notion of the museum as a space of accumulation, a throwback to the 19th century and its rapid industrial and capitalist expansion; a place of connoisseurship or objects and artifacts for a specific elite or class (one is reminded of what Heidegger argued was the problem with artwork being displayed in galleries and not in public where persons can experience art in its “happening of truth.”) The ROM rarely engages a person or provokes them to think, to critically engage them, rather than making them feel they are walking through a collection of curios.